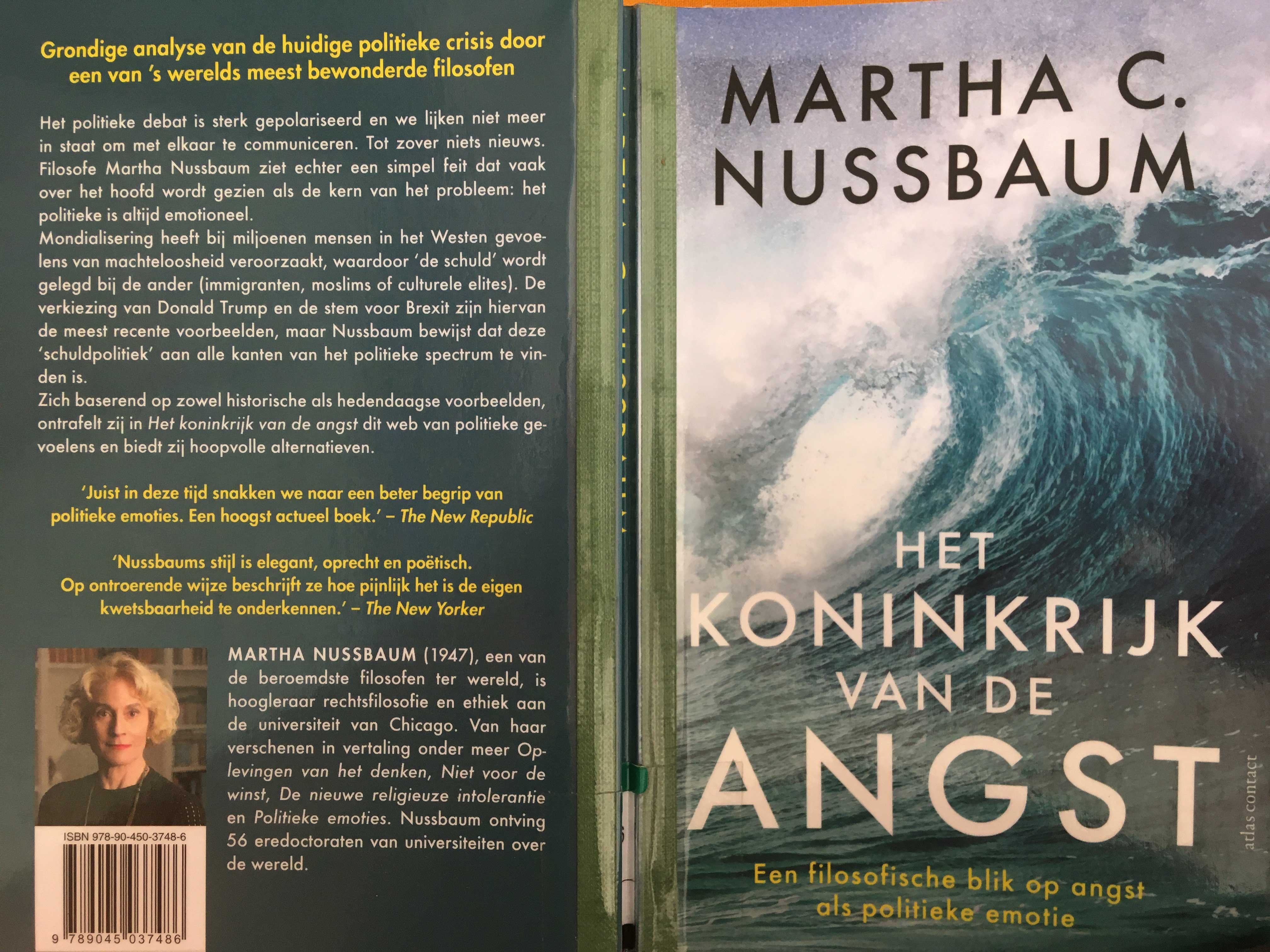

Naked and Afraid

By Martha Nussbaum

By Martha Nussbaum, from The Monarchy of Fear, which was published last month by Simon and Schuster. Nussbaum is a professor of law and philosophy at the University of Chicago and the author of more than twenty books. Source

You are lying on your back in the dark. You see, you hear, you feel, but you can’t act. You are completely, simply, helpless.

This is the stuff of nightmares. Most of us have nightmares of helplessness, in which we feel a terrible fear of inescapable demons pursuing us—and perhaps an even greater fear of our own powerlessness. But this horror story is also the condition of every human baby. Calves, foals, chicks, puppies, baby elephants and dolphins—almost all other animals learn to move very quickly, more or less right after birth. Only human beings remain helpless for years, and only we survive that helpless condition. As Lucretius, the Roman poet of the first century bc, wrote,

the baby, like a sailor cast forth from the fierce waves, lies naked on the ground, unable to speak, in need of every sort of help to stay alive, when first nature casts it forth with birth contractions from its mother’s womb into the shores of light. And it fills the whole place with mournful weeping, as is fitting for one to whom such trouble remains in life.

Politics begins where we begin. Most political philosophers have been male, and even if they had children they did not typically spend time with them or observe them closely. Lucretius’ poetic imagination led him to places where his life probably did not. But philosophy made big strides when one of democracy’s great early theorists, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a major intellectual architect of the revolutionary anti-monarchical politics of the eighteenth century, wrote about the education of children with a deep understanding of the psychology of infancy. Rousseau was the opposite of a loving parent: he sent his children to a foundling hospital, without even recording their dates of birth. Somehow, though, through his various experiments in teaching other people’s young children, through conversations with women, through memories of his childhood, through his close reading of Lucretius and other Roman philosophers, and through his own poetic imagination, he understood that early need creates problems for the type of political order he sought. He understood the dangers this condition posed for the democratic project.

Human life, Rousseau understood, begins not in democracy but in monarchy. The baby has no way of surviving except through reliance on caretakers—and so it makes slaves of others. Babies must either rule or die. Incapable of shared work or reciprocity, they receive what they need only by commands and threats, and by exploiting the worshipful love given them by others. (In letters, Rousseau made it clear that this was why he abandoned his children: he didn’t have time to be at a baby’s beck and call.)

We come into a world with which we are not ready to cope. The discrepancy between the very slow physical development of the human infant and its rapid cognitive development makes fear the defining emotion of infancy. Adults are amused by the baby’s futile kicking and undisturbed by its crying because they know they are going to feed, clothe, protect, and nurture it. The infant, however, knows nothing of trust, regularity, or security. Its limited experience and short time horizons mean that only the present torment is fully real, and moments of reassurance, fleeting and unstable, quickly lead back to insufficiency and terror. Even joy is tainted by anxiety, since to the infant it seems all too likely to slip away.

We usually survive this condition. We do not survive it without being formed, and deformed, by it. Neurological research on fear has shown that the scars of early fright stimuli endure and become a continuing influence on daily life.

Fear is not only the earliest emotion in human life; it is also the most broadly shared within the animal kingdom. To experience other emotions, such as compassion, you need a sophisticated set of thoughts: that someone else is suffering, that the suffering is bad, that it would be good for it to be relieved. But to have fear, all you need is an awareness of danger looming. The thoughts involved don’t require language, only perception and some vague sense of one’s own good or ill.

Fear is not just primitive; it is also asocial. When we feel compassion, we are turned outward: we think of what is happening to others and what is causing it. But you don’t need society to have fear; you need only yourself and a threatening world. Indeed, fear is intensely narcissistic. An infant’s fear is entirely focused on its own body. Even when, later on, we become capable of concern for others, fear often drives that concern away, returning us to infantile solipsism.

Marcel Proust, in In Search of Lost Time, imagines a child, his narrator, who remains unusually prone to fear, especially at bedtime. Young Marcel’s terror compels him to demand that his mother come to his room and stay as late as possible. His fear inspires in him a need to control others. He has no interest in what would make his mother happy. Dominated by fear, he needs her to be at his command. This pattern marks all his subsequent relationships, particularly that with Albertine, his great love. He cannot stand Albertine’s independence. It makes him too anxious. Lack of full control makes him crazy with fear and jealousy. The unfortunate result, which he narrates with great self-knowledge, is that he feels secure with Albertine only when she is asleep. He never really loves her as she is, because as she is she is not his own.

Proust supports Rousseau’s point that fear is the emotion of an absolute monarch who cares about nothing and nobody else. This is not the case for other animals, which are capable of acting independently almost as soon as they are capable of feeling fear. Their fear in infancy, so far as we can tell, remains within bounds and doesn’t impede concern for and cooperation with others. Elephants, for example, which are famously communal and altruistic, act reciprocally with their herd almost from birth. Young elephants may run to adult females for comfort, but they also play games with others and gradually learn a rich emotional vocabulary. The powerless human baby, on the other hand, can only terrorize others.

In childhood, concern, love, and reciprocity are staggering achievements, won against fierce opposition. Donald Winnicott, a great psychoanalyst and pediatrician, invented a concept for what children need if they are to develop concern for others. He called these conditions the facilitating environment. Applying this idea to the family, he showed that the home must have a core of basic loving stability and must be free from sadism and child abuse. But the facilitating environment has economic and social preconditions as well: there must be basic freedom from violence and chaos, from fear of ethnic persecution and terror; there must be enough to eat and basic health care. Working with children who were evacuated from war zones, he understood the psychic costs of external chaos. He recognized that an individual’s ability to reach outward is inflected by political concerns, that the personal and the political are inseparable. Winnicott kept returning to political questions throughout his career. What should we be striving for as a nation if we want children to become capable of reciprocity and happiness?

Winnicott thought that people could attain “mature interdependence” if they had a facilitating environment. His focus was on attaining such an environment in the individual child’s life in the family. But his wartime work led him to speculate about the larger question: What would it be like for society as a whole to be a facilitating environment for the cultivation of its people and their human relationships?

Such a society, he thought (as the Cold War advanced), would have to be a freedom–protecting democracy, since only that form of society fully and equally nourished people’s capacities to grow, play, act, and express themselves. Winnicott thought that a key job of government was to support families. Families cannot make children secure and balanced, capable of withstanding onslaughts of fear, if they are hungry or if they lack medical care, if they lack good schools and a safe neighborhood environment. He repeatedly connected democracy with psychic health: to live with others on terms of mutual interdependence and equality, people have to transcend the narcissism in which we all start life. We have to renounce the wish to enslave others, substituting concern, goodwill, and the acceptance of limits for infantile aggression.

But how? It’s an urgent question, and the stakes are high. Fear always simmers beneath the surface of moral concern, and it threatens to destabilize democracy. Right now, fear is running rampant in our nation: fear of declining living standards, of unemployment, of the absence of health care in times of need; fear of an end to the American dream, in which you can be confident that hard work brings a decent and stable life and that your children will do better than you did if they, too, work hard.

Our narrative of fear tells us that very bad things can happen. Citizens may become indifferent to truth and prefer the comfort of an insulating group of peers who repeat one another’s falsehoods. They may become afraid of speaking out, preferring the comfort of a leader who gives them a womblike feeling of safety. And they may become aggressive against others, blaming them for the pain of fear.

When the underlying facts are right, fear can be a useful guide in many areas of democratic life. Fear of terrorism, fear of unsafe highways and bridges, fear of the loss of freedom itself: all of these can prompt useful protective action. But directed to the very future of the democratic project itself, a fearful approach is likely to be dangerous, leading people to seek autocratic control or the protection of someone who will control outcomes for them. Martin Luther King Jr. understood that a fearful approach to the future of race relations would play straight into the hands of those who sought to manage things by violence, a kind of preemptive strike. His emphasis on hope was an attempt to flip the switch, getting people to dwell mentally on good outcomes that could come about through peaceful work and cooperation.

Hope is the inverse of fear. Both react to uncertainty, but in opposing ways. Hope expands and surges forward, fear shrinks back. Hope is vulnerable, fear is self-protective. This is the difference.

The Guardian review